One of the best, and certainly the least used of the genealogical sources for Canton Vaud is the terriers, compilations of feudal obligations relating to land. The terriers, often of a type called "grosses de reconnaissances", were used right up to the end of the feudal system, which occurred officially in the new Canton of Vaud in 1804. In May, 2009, the Archives Cantonales Vaudoises (ACV) and FamilySearch.org announced a project to digitize the terriers—eventually, all 4,300 volumes, approximately 1.6 million images—and make them available on the internet. The Cercle Vaudois de Généalogie posted an announcement regarding the project. In June, 2011, the first results of this project were added to the FamilySearch.org web site. At the present time, images from some of the terriers are available. The images are not yet indexed. Even though the project has a long way to go, it is not too soon to learn something about these records.

As of June 22, 2011, about 2/3 of the terriers for the district of Aigle, plus one fragment from the district of Avenches, were available on the FamilySearch.org web site.

Indexes and abstracts from a large number of terriers that have not yet been posted on the FamilySearch web site are available here.

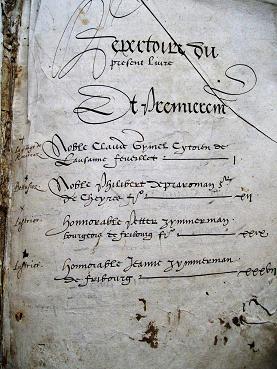

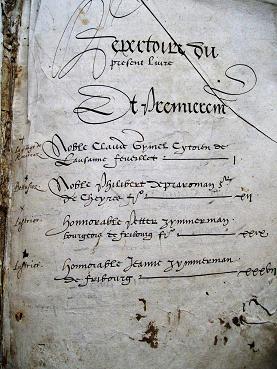

Why are the terriers important? They are simply the best source for genealogical information in the feudal era, second only to the church records (available on microfilm through the Family History Library as well as at the ACV). When your research leads you back to a time when the church records do not provide the clues you need, the next place you should look is the terriers. In my opinion, the terriers are even more helpful than the records of the notaries (also on microfilm through the Family History Library and at the ACV), because most of the terriers have a simple index or table of contents ("Répertoire"), and a much greater fraction of the terriers seem to have survived, compared with the registers of the notaries. Also, the terriers, unlike any other resource in the Pays de Vaud, usually give the history of ownership of each parcel of land, in a way that often gives two or three generations of genealogy, and sometimes as many as five or six generations.

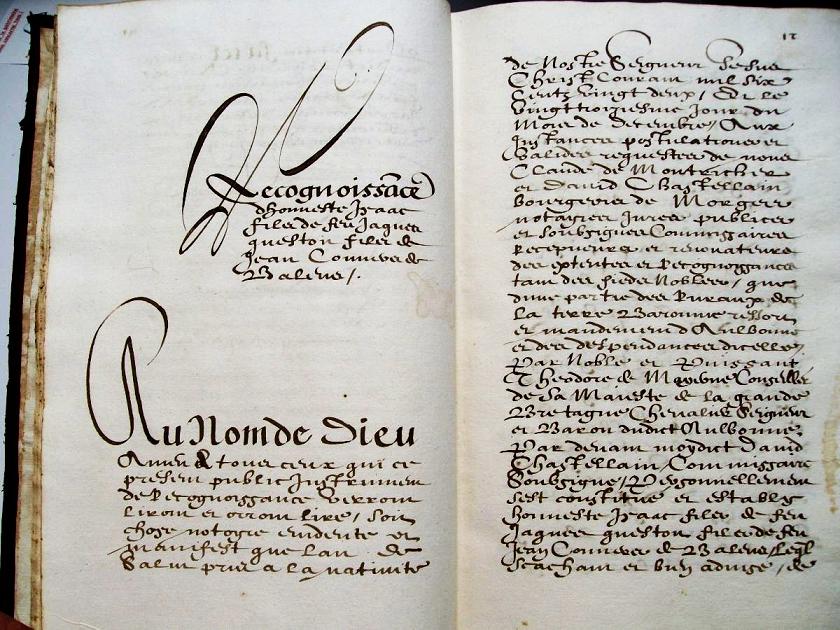

What is in a terrier? Most of the terriers consist of contracts called "reconnaissances", in which a person, or sometimes an institution, "recognizes" an obligation to a person or an institution that is one step higher in the feudal pecking order. A person at the lower rank in the feudal pecking order is a "vassal"; a person at the higher rank is a "seigneur". The "seigneur" holds title (granted by some even higher-ranking "seigneur") to one or more pieces of real estate that he or his predecessors had granted to the vassal (or the vassal's predecessors) in return for an obligation of some kind, frequently an annual payment of money, grain, livestock, etc. The predecessors of either the seigneur or the vassal might be their respective ancestors (in which case, the property was inherited by the seigneur from his ancestors, or by the vassal from his ancestors, or both), or the property might have been sold, rented, mortgaged, etc. by either party, or it might have derived from a marriage settlement on either side, etc. For the genealogist, it is usually the history of the vassal that is most important. The "reconnaissance", then, says that, at the request of the seigneur, the vassal has appeared before the "commissaire" who is compiling the terrier, and "recognizes" his obligation to the seigneur for specific pieces of land and for specific amounts of money or other obligations. The individual pieces of land are described with reference to adjacent properties, and also with reference to the names of the vassals who recognized the same obligations in the past (frequently giving the date and the name of the commissaire of the reconnaissance in the previous terrier). Further, the reconnaissance will usually indicate how the vassal acquired the property: by "legitimate succession" (inheritance), by a sale, etc. The reconnaissance closes with the names of witnesses and the signature of the commissaire. These documents are verbose, but the phraseology tends to be very similar from one document to the next. The form of the reconnaissance is so predictable, in fact, that it scarcely matters whether it is in French (after the Reformation) or in Latin (before the Reformation). The script is usually large and legible.

How do I find the right terrier? With over 4,300 volumes to choose from just at the ACV, and many additional volumes still at the various communal archives, it is sometimes difficult to know where to start. The ACV has grouped the terriers by district, although the patchwork of feudal land ownership does not always coincide with district boundaries. For each nominal district (such as Aubonne, Morges, etc., the same districts used to classify the records of the notaries), the ACV has an inventory containing detailed descriptions of each terrier. The descriptions include the approximate date of the terrier, the name of the seigneur or institution for which it was compiled, the names of the commissaires, the names of the communes where the properties were located, the number of pages, whether or not the volume has an index, and other details. There is also a series of volumes that list the available terriers by date for each village. Because the boundaries of the Pays de Vaud were different under the anciens régimes (Savoie, Bern), the terriers actually cover a number of villages that are no longer part of Vaud, especially in the Vully region. Here are the links to the inventories:

How reliable are the terriers? Like other documents written by human hands, the terriers contain errors. The same caveat applies to church records, the records of the notaries, and other sources. Because errors are possible, it is important to search as widely as possible. If you can locate multiple citations that agree on a particular genealogical fact, you have a better chance of reaching correct conclusions. Fortunately, the Pays de Vaud was divided into an enormous number of small parcels of land which had been divided, inherited, exchanged, bequeathed, mortaged, forfeited, and otherwise shuffled about, with the result that any given vassal probably had obligations to several different seigneurs, each one compiling a separate terrier about once a generation. It is not unusual to find the same person making a reconnaissance in several different terriers over a period of several decades, and with genealogical information in each such reconnaissance. Further, genealogical details are often mentioned in the descriptions of adjoining properties, so it is sometimes possible to locate multiple paraphrases of earlier reconnaissances, which can be compared for consistency. Because of the inherent redundancy of the terriers, it is possible to spot inconsistencies, and frequently to resolve them.

The terriers present a special difficulty when they paraphrase earlier reconnaissances. It is often difficult to be sure who was alive and who was dead at a specific date in the past (information paraphrased from an earlier terrier), and often there is no date given for events in the distant past. Often, however, there is enough information to lead you to the next earlier terrier, if it still exists. By finding the next earlier terrier, you can often compare the earlier reconnaissance with its later paraphrase, and thus better understand what the compiler of the later terrier was trying to tell you about the history of the property and of the family that owned it.

The terriers may reveal changes of family names. Genealogists who are familiar with the church records of the Pays de Vaud will have encountered "dit names" or aliases, a situation where a particular family might be known by more than one surname. This practice, probably arising from the practical need to distinguish individual families who happened to have the same name in a small village, was especially prevalent before about 1600. In the village of Gimel, for example, we find multiple aliases for most of the families in the earliest church records. The terriers go back much further. By reading the terriers carefully, we can sometimes spot historical changes of family names, and occasionally we can identify the particular person who was the source of the new name. The multi-generational character of the terriers makes them the best source for finding these situations.

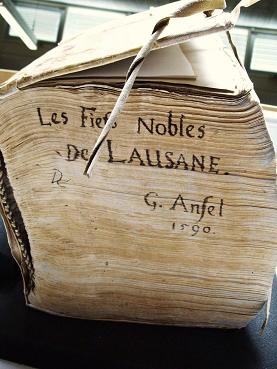

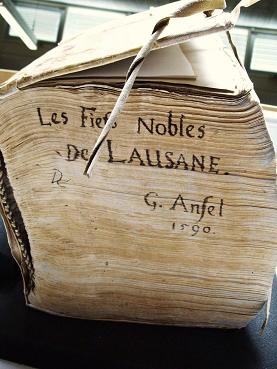

Who uses terriers for genealogical research? Oddly, very few of the genealogies that have been compiled for families from Canton Vaud have made much use of the terriers. We know this because it has been so easy to find proof that the published genealogies are incorrect. For example, the father of the Magdelaine Gachet who married Samuel d'Erlach of Bern—this couple is cited many times in the early 17th Century—was unanimously given as Nicolas Gatschet of Bern, in spite of the fact that Nicolas left a very legible and detailed account of his family, indicating that his daughter Magdelena died as a young child. The true parentage, already deduced from the rest of the story of the Gachet/Gatschet family as reported in the records of the notaries, was finally found in a terrier for the "noble fiefs" of Lausanne. Her father was François Gachet, one of the six brothers of Nicolas. Another example is found in the publications on the noble de Mont family of Aubonne by Louis de Charrière, who speculated about the identity of some of the last members of that family cited in various records around 1600. The correct parentage of noble Gabrielle de Mont, wife of the notary Antoine Mayor of Ballens, is revealed in the terriers. The terriers have also revealed that the Favre family of Gimel circa 1580 was known in earlier generations as de Genève dit Billiard; that Mayor of Mollens derives from Claude Mayor of Ballens (we are still trying to find the parentage of this Claude Mayor); that the Monod family of Ballens apparently derives from an Aymonet Mayor of Ballens whose descendants were known as "dit Monod" and then as Monod; that the Mayor family of Ballens was originally an alias (or vice versa) of du Verney, etc. A thorough search of the terriers would have brought these facts to light long ago. Were the terriers hidden away in communal or other archives where genealogists did not have access to them? Did genealogists believe that they had all been destroyed during the "Bourla-Papey" incident in 1802? Were they too difficult to use before the ACV compiled its inventory and finding aids? Or were they just forgotten? Considering the extensive use that has been made of other records from the medieval period, it is difficult to understand why we find so few citations of these important records.

Even in the cases where we find a few citations to the terriers, it has not taken us very long to find additional information in other terriers. Apparently, these genealogists were satisfied to find one or two specific answers, then stopped searching. In our experience, a limited search will not yield the full story, and it runs the risk of yielding information that is incorrect or seriously incomplete. Therefore, when the terriers are available to a wider audience, it is very likely that many genealogies will have to be revised, and many more will be extended a century or more into the past, in short order.

How do I cite information found in the terriers? During the preparation for the project, each page of to be photographed was numbered, thus making every image within each terrier identifiable. Page numbers in the "répertoire" section, if the terrier has such a section, are prefixed by the letter R. If the terrier has "foliation" — that is, the older numbering was on the front side of each sheet only — the back side of each sheet is the same as the number on the front, but with the letter v appended. Thus, the back side of folio 8 will be designated 8v. Most of the earlier terriers used the foliation system, numbering only the front side of each sheet. Later terriers, beginning perhaps after 1750, used the pagination system, so that each side is numbered sequentially. However, the terriers contain all sorts of irregularities in foliation or pagination, probably the result of ancient clerks becoming bored and losing count, or due to rearrangements of the contents of a terrier, or the loss or removal of some sections, during binding or rebinding. There may be multiple attempts at numbering, in roman or arabic numberals. It seems best to follow the modern numbers, in pencil, whenever possible. A complete citation, then, would consist of the following: ACV Fx NNN, fol. zzz. The designation ACV tells us that the document is from the Archives Cantonales Vaudoises, the Fx NNN number is the classification of the volume at the ACV, and fol. or p. zzz tells us the folio number or page number at the top of the image.

To this we should add the title of the terrier. Since the actual titles of these volumes are in many cases extremely verbose, a short title will suffice. Include the name of the "commissaire" who compiled the volume, if known.

Then we have to add the date of the particular "reconnaissance", if available. Most of the terriers have a date pertaining to each separate reconnaissance, usually at the beginning of the reconnaissance, or else at the end. Occasionally the date is in the middle, after a long section of preliminary text, or we may find a designation such as "date comme dessus", "l'an et jour prémis", etc., indicating that we have to look at the previous reconnaissance in the same volume to locate the date. Or, in some volumes, the individual reconnaissances are not dated at all, and we have to rely on a date found in the introduction, or even on a date found on the spine of the volume, or an estimated date from the ACV's inventory. After adding the date to the citation, we can make it even more informative by adding the title of the individual reconnaissance, such as "Reconnaissance de Jean Favre, bourgeois d'Orbe".

By habitually citing information from the terriers and other documents from the ACV in this way, we make it possible for anyone, whether scholar or amateur, American or Swiss, to identify the original source easily.

Navigating through the images. Probably for some good reason, the indexes that are normally found at the beginning of each terrier have been relcated to the end of the images for each volume! The first image for each terrier is normally a description of the volume, taken from the ACV's inventories. When you want to browse through the images of a terrier that has not been indexed, review the first image to understand the nature of the volume, then go to the last image to find the end of the index, if there is one.

As more information about the digitization project is announced, we will post it here.

—John W. McCoy.